Artificial Intelligence (AI) has found its way onto the Carnatic concert stage — truly ‘All-Invasive’ (AI), one might say. Just two days after ChatGPT made its debut as a pallavi composer at Pallavi Darbar 2025 (July 2 — 6), though, the spotlight swung back to tradition.

Under the auspices of Carnatica and Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha, disciples of vocalist-violinist Delhi P. Sunder Rajan revisited and reimagined pallavis, crafted by past masters and their guru. The event, organised as part of the annual Pallavi Darbar festival, was held at Srinivasa Sastri Hall.

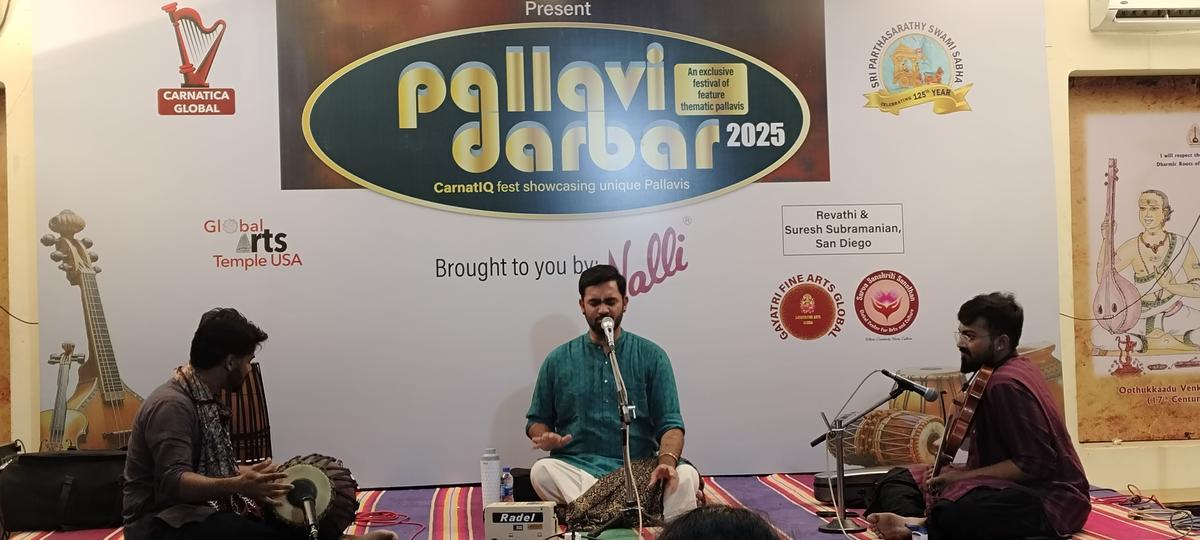

Pallavi Darbar festival

R. Akshay Ram (mridangam), R.P. Shravan, Shruthi Shankar Kumar, Dhanya Rudrapatnam, Padmashree Srinivasan and Chidambaram G. Badrinath.

| Video Credit:

Carnatica/Special Arrangement

Shruthi Shankar Kumar, R.P. Shravan, Padmashree Srinivasan and Dhanya Rudrapatnam not only rendered a curated array of pallavis with flair, but also articulated their structural and aesthetic features with endearing clarity. A reminder, perhaps, that in Carnatic music, timelessness and evolution are but two sides of the same coin.

Of the nine pallavis presented, four were by T.R. Subramaniam.

| Photo Credit:

K.V. SRINIVASAN

The programme titled ‘Pallavi Memoirs’ saw the quartet present nine pieces, with Chidambaram G. Badrinath on the violin and R. Akshay Ram on the mridangam providing enthusiastic support. Of the nine selected, four were composed by T.R. Subramaniam, a pioneering one by M. Balamuralikrishna and four by Sunder Rajan. Given the focus was on the pallavi structure, the traditional trikalam and tisram were demonstrated where relevant, and manodharma was kept minimal.

Balamuralikrishna’s Mukhi pallavis

Known for his inventive, populist approaches to pallavi, Subramaniam brought a fresh energy to the form. Balamuralikrishna, on the other hand, enriched the rhythmic canvas with his Mukhi pallavis, opening up new exploratory possibilities within the Carnatic idiom. The main pallavi, composed by Sunder Rajan, was a creative expansion of Balamuralikrishna’s Mukhi concept.

The show included a pioneering pallavi composed by M. Balamuralikrishna.

| Photo Credit:

GANESAN V

Though it came later in the recital, the conceptual high point merits early attention here. As a tribute to Balamuralikrishna on his 95th birth anniversary, the team offered a brief presentation of the maestro’s well-known Panchamukhi Adi tala pallavi in Kalyani ‘Sangeetha laya jnaanamu, sakala sowbhagyamu’. Balamuralikrishna devised the Mukhi talas — Trimukhi, Panchamukhi, Saptamukhi, and Navamukhi — by applying different gatis (rhythmic subdivisions) to the two components of a Suladi tala: sa-shabda (with sound) and ni-shabda (without sound). In these talas, only the sa-shabda kriyas (e.g., beats 1, 5, and 7 in Adi tala) adopt a nadai other than chatusram, while the rest of the cycle retains its base structure. The tala derives its name from the nadai applied to these audible beats: tisram (Trimukhi), khandam (Panchamukhi), misram (Saptamukhi), and sankeernam (Navamukhi).

Inspired by the concept, Sunder Rajan composed a Gati-traya Bahumukhi pallavi (featuring three gatis and multiple rhythmic dimensions) in Charukesi, set to Misra Triputa tala. Following a succinct raga alapana by Dhanya, mirrored on the violin by Badrinath, Shravan rendered the tanam. The intricate pallavi ‘Eesanai mahesanai ninai, trinethranai pavithranai jaga(deesanai)’ was executed with poise by the disciples. Its vibrant rhythmic fabric incorporated tisra (first beat), khanda (eighth) and misra (10th) gatis in the sa-shabda sections, representing the confluence of the three gatis. A short burst of kalpanaswaras followed, with Akshay Ram capping the piece with a crisp, energetic tani avartanam.

The recital opened with three consecutive pallavis by Subramaniam. The first in Pantuvarali ‘Sambho mahadeva vibho paahi prabho, santatam swayambho’ was set to Misra Triputa. The uttarangam featured a Gopuccha yati — a tapering sequence of syllables resembling the shape of a cow’s tail — beginning with ‘santatam’ (seven counts), followed by ‘swayambho’ (6), and continuing into the purvangam with ‘sambho’ (5) and ‘maha’ (4).

Interesting addition

Delhi P. Sunder Rajan’s disciples presented four pallavis composed by him.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

A Bilahari sketch by Shruthi preceded the next pallavi ‘Raghukula tilakudai velasina ramachandrude, maa paali devudu sri’ set to Khanda Triputa. The embedded trikalam in each of the first three words — in a 4:2:1 ratio — was aesthetically executed, as was the tisram. The inverse ratio singing (1:2:4) was an interesting addition.

The Kiravani pallavi, ‘Vallee deva senapathe, namo namasthe’ had a tanam prelude by Padmashree. Set to Khanda Triputa, this pallavi featured a receding mathematical pattern in the purvangam: ‘vallee’ – 4,4 counts; ‘deva’ – 3,3; and ‘senapathe’ – 2,2. In the uttarangam, namo – 1,4; namasthe – 1,4; and 1,4 (the final 4 transitioning into the purvangam). After trikalam in chatusra and tisra nadais, pratilomam was performed from the arudhi — an uncommon but intriguing choice. The swara garland, besides Kiravani, included Valaji (Dhanya), Abheri (Shruthi), Shanmukhapriya (Shravan), Mohanakalyani (Padmashree) and Vasanthi (Badrinath).

The next three presented were those of Sunder Rajan. The Saveri pallavi in 2-kalai Adi tala ‘Kumara (3 syllables) gurupara (4) karthike(ya) (5), ninadhupadhamalar (7) panivome (5), showcased elegant ascending and descending patterns. The purvangam built up as 1 matra X 3 syllables, 2X4, and 3X5, while the uttarangam traced a descending sequence — 3X7, 2X5, and finally 1X3 (returning to ‘Kumara’).

‘Venkataramana, sankataharana tirupati’ in Lathangi set to Khanda Jhampa, had the purvangam in Tisra nadai (3X5) and uttarangam in Khanda nadai (5X3), and was well-executed along with trikalam in Chatusra tisram and pratilomam. The swarakshara pallavi in Khamas ‘Saamagaana lola nin paadhame gathi, mahadeva sadasiva nidham panindhen’, set to Adi tala in Khanda nadai, was presented in four speeds — keezh, chatusra-tisram, samam and mel.

The concluding number — a Surutti pallavi in Sankeerna Jhampa tala (Tisra nadai) ‘Velan sivabalan varagunaseelan, vallee lolan’, composed by Subramaniam, was structured in Srotovaha yati, the ascending counterpart to Gopuccha yati, evoking the image of a river that begins as a trickle and gradually widens. The quartet performed Chatusram to this Tisra nadai pallavi with assurance.

Novel experiment with ChatGPT

Ashwath Narayanan presented a four-raga pallavi, that had been composed with the help of ChatGPT.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The audience at Ashwath Narayanan’s concert at Pallavi Darbar was in for an unexpected revelation. The acrostic pallavi in Tamil that he presented in four ragas had been composed with the help of ChatGPT — marking a novel intersection of technology and tradition in the evolving landscape of Carnatic music.

An acrostic pallavi is one in which the first syllables or letters of each word or line of text form a meaningful word or phrase. In this instance, the structure was designed to yield four raga names — Ananda Bhairavi, Vasantha Bhairavi, Saalaga Bhairavi, and Sindhu Bhairavi. The purvangam (first half) contained text whose opening syllables of the words spelt out the respective raga names (excluding the common suffix ‘Bhairavi’), while the lyric of the shared uttarangam (latter half) gave out ‘Bhairavi’.

The lyrics ran as follows:

‘Adinaan nandagopan thanayan, painkuzhalaada rasamigavaagi vinaigal-arave’ (Ananda Bhairavi);

‘Vadamathurai sannidhiyil thavazhndhaadinaan’ (Vasantha Bhairavi);

‘Saarangan layamodu gathiththaadinaan’ (Saalaga Bhairavi); and

‘Silambaadinaan dhuvaarakaapurisan’ (Sindhu Bhairavi).

Ashwath said that, not being someone with a flair for lyric-writing, he had turned to the AI tool for assistance. Given the pallavi’s multi-raga structure, he added, he chose to focus primarily on the melodic aspect, keeping the rhythmic framework deliberately simple (Misra Chapu).

The composition followed the acrostic structure closely in the first three segments, but the fourth — Sindhu Bhairavi — featured a minor lapse, with the middle syllable ‘n’ of ‘Sindhu’ not represented in the lyric. Nevertheless, the experiment stood out for its creativity.